That’s where I first saw Mary,

On that roadside picking blackberries,

That summer I turned a corner in my soul,

Down that red dirt road

Brooks and Dunn (2003)

Some days my song references and links to my morning notes can be a little more nuanced and today is one of those.

The aforementioned song is by a favourite of mine, by Brooks and Dunn, and references an area where they both drank their first beer, found love, crashed their first car, found Jesus and learned that “happiness on Earth ain’t just for high achievers”.

It’s also very catchy and enjoyable, so the song would be worth a reference without any parallels with today’s note.

I wrote part 1 of my series on bank funding and capital last week mentioning Nelly Furtado’s lyric “… you don’t know me that well” to describe the inner workings of Australian banks’ funding profiles and lack of knowledge regarding the different ways that banks fund themselves.

Today I reference Monday’s note about turning a psychological corner through the changing of the season to spring, but I also want to channel my own past, in the areas of bank liquidity and capital – where I originally worked at National Australia Bank – and set myself upon this “red dirt road” that has led my career to writing this note today.

Understanding banks and their capital requirements

Over the past 40 years, capital markets have grown faster than banks have, meaning that banks’ share of providing credit to households and business has dropped.

Bank of International Settlement (BIS) data updated 14 September shows that banks’ share of credit has dropped from 55% to 34% over this 40-year period.

However, banking institutions remain a critical part of the financial system, and the overall global economy. Banks operate payments systems, supply credit and serve as agents and arrangers for a wide range of financial transactions.

As a result, their well-being and resiliency remains a key concern, and banks are required to maintain sufficient capital to weather loan defaults and declines in asset values that eventually come in each economic cycle – something we’re experiencing right now during the COVID-19 recession.

What is capital?

Capital is a form of self-insurance that provides a buffer against unforeseen losses and is an incentive to manage risk-taking.

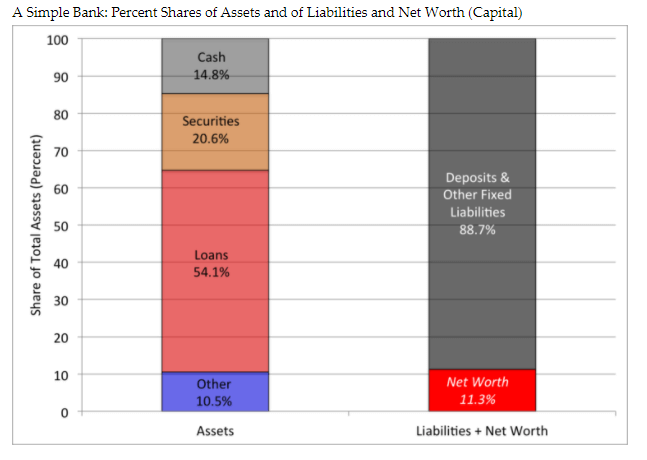

In accounting terms, capital is the residual value that remains after subtracting a bank’s fixed liabilities from its assets. It is sometimes called “net worth” for this reason.

Capital is considered a “liability” as it is owed to the bank’s owners (shareholders) after liquidating all assets.

However, it is the buffer that separates a bank from insolvency, at which point its liabilities would exceed the value of its assets.

Source: US Federal Reserve Bank, H.8. for US Commercial Banks

Current levels of capital – using CBA as example

Much like the changes in funding we discussed in part 1, capital requirements have become more highly regulated since the 2007/2008 financial crisis through accords such as Basel III, with more focus from domestic regulator APRA on our own banking institutions’ levels of capital.

This focus on capital was a global response to the collapse of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, both of whom had issues with their overall levels of capital, leverage and liquidity. Not only were they under-capitalised, they were also overly leveraged and had little liquidity.

The effect of this response was for banks to widen the gap between the sum of their risk-weighted assets (loans and investments) and their liabilities.

This is known as deleveraging.

Deleveraging can be done in several ways:

- Banks can reduce the riskiness of their assets by selling off their riskier loans, decreasing the size of such loans, or by investing in safer assets

- Banks can raise additional equity by rights issues

- Banks can issue special types of bonds that are convertible to equity (“Hybrid”) or that can be written down to lower values (“Tier 2”)

In essence, banks needed to raise more capital in proportion to the size of their asset base.

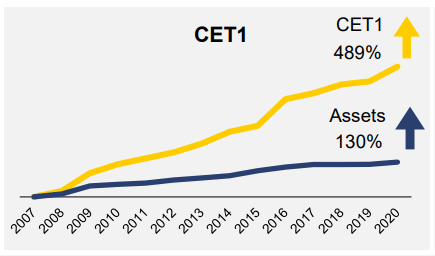

For example, CBA has increased their Common Equity/Tier 1 Capital ratio (CET1) 489% since the GFC compared to a 130% increase in their risk-weighted assets.

Source: CBA

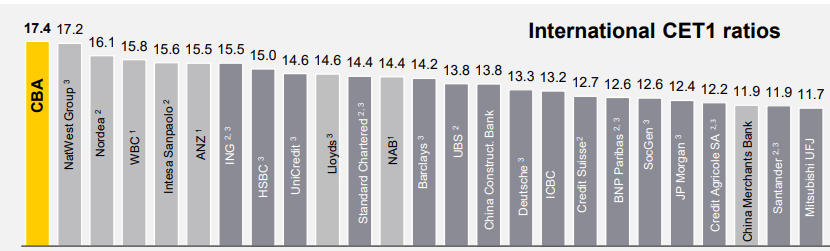

In the case of our big 4 banks – ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac – APRA requires the four banks be “unquestionably strong”, adding an additional layer of capitalisation compared to most banks.

APRA requires these big four banks to be highly capitalised due to their essential nature to the Australian economy, and the “too big to fail” nature of their businesses.

Because of this, our big 4 banks are among the most highly capitalised banks in the world

Source: CBA, Morgan Stanley, cropped to fit page size

Types of capital

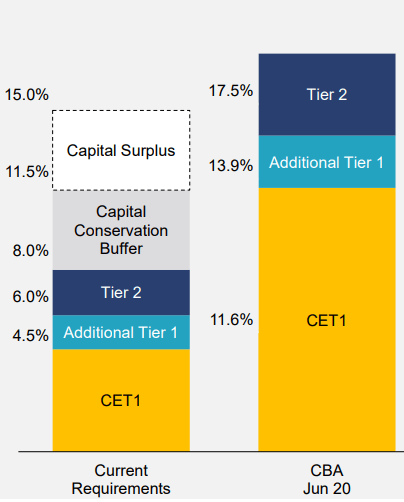

To create these capital buffers, new forms of securities have been created for their Loss Absorbing Capacity (LAC).

I.e. if a bank was to see higher credit losses as a result of customers defaulting on loans due to financial hardship, there would be sufficient LAC (capital) as a buffer, so that customer deposits are not required to pay-off losses.

These securities have now become common-place and are called names such as “hybrid”, “tier 2”, “Additional T1 (AT1)” and “Total Loss Absorption Capital (TLAC)”.

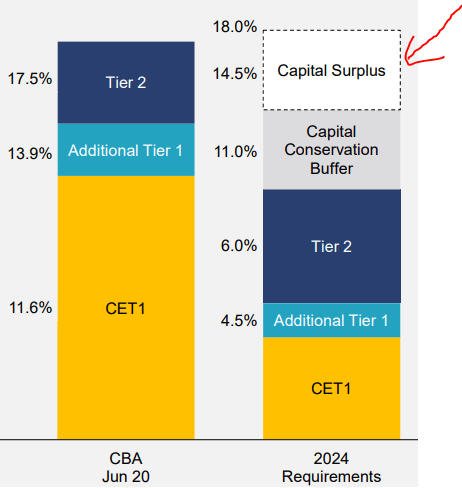

In CBA’s case, they have a large capital buffer through common equity (shares) outstanding, but also have a sizeable Additional Tier 1 (think: hybrid securities such as CBAPD) and Tier 2 (subordinated) securities outstanding.

Source: CBA

The way these securities work is that if the issuing bank incurs losses, the capital will be written down (be valued at a lower amount).

i.e. a hybrid security could be converted to equity in order to increase CET1

i.e. bond holders incur losses, not taxpayers (bail out) or deposit holders

Has “too big to fail” been solved?

The too big to fail status is still a hot topic as banks such as JP Morgan argue they are over-capitalised, while financial regulators such as the US Federal Reserve argue they are under capitalised.

From the bank point of view, they have raised capital which has costs associated with it. These costs come in the form of higher dividend and distribution payments and higher bond payments (coupons).

Regulators are seeking to ensure that taxpayers do not bear the burden of bailing out banking institutions in the next crisis.

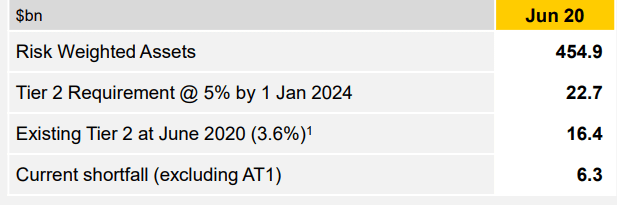

In our case APRA requires an additional 3% of risk-weighted assets in total capital from our big 4 major banks by January 2024.

Source: CBA

In CBA’s case, this would require an additional 6.3bio AUD of LAC by this date.

Source: CBA

Finally, I recommend reading the above letter from the US Federal Reserve to JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon.

Dr. Kashkari of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve bank – who votes in US interest rate decisions – makes the point that bank capital needs to be raised to see a shift in risk-taking behaviour, which is something APRA seems to agree with.

Regardless of our personal opinions, this will mean that Australian banks continue to raise capital during COVID-19, but also in the years to come to meet the 2024 regulatory requirements.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.