Each year there is a large gathering of economists, financial market participants, academics, US government officials in Jackson Hole, Wyoming (USA), to discuss long-term economic policy issues of mutual concern. All the papers are available online.

This year’s meetings occurred last week, with the key speech from Federal Reserve Chairperson Jerome Powell on our Friday morning.

There are typically 120 persons in attendance with the audience composition tailored to the following numbers:

- 45 central bankers

- 25 Federal Reserve System employees

- 24 Academics

- 12 Media/Journalists

- 5 Government

- 5 Financial organisation representatives

(For the maths gurus, we don’t find out who the other 4 people are.)

It is obvious who the target audience is, with emphasis towards central bankers of similar thought, with little “real world” representation, i.e. the people that feel the real-world effects of central bank policy, and often economists of different orthodoxies are not invited.

This year, Fed chair Powell didn’t disappoint those waiting on his speech, by delivering his intention to let the US economy run hot, in even more forceful fashion than generally anticipated.

To me, this had parallels to U2’s 1984 power ballad “Pride”, which while about the US civil rights movement, describes actions that cause harm though intended to be helpful “in the name of love”.

The change in Federal Reserve Policy

What became newsworthy was the Fed adopting a formal shift to a symmetric or average inflation targeting regime, while retaining their 2%* inflation target.

“…we will seek to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time. Therefore, following periods when inflation has been running below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

All this adds up to a view that the Fed Funds rate (the US cash rate) is going nowhere until the Fed can see 2%+ inflation or possibly more, something currently not forecast through market pricing for another 4 years from now.

I have some issues with this change in policy.

No real change in policy

While Mr Powell’s speech was a formal adoption of this policy, this policy has already been in place for some time for those that read the FOMC’s monthly statements, in fact, every statement this year to date.

For example (emphasis mine):

“The Committee judges that the current stance of monetary policy is appropriate to support sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation returning to the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective.”

We just didn’t notice.

I have ten reasons why I question this re-wording of policy

1. Using average inflation as your guide means that you need to be dependent upon historical changes in price, and past movements should have no bearing on future price changes.

If we see inflation of 1% in 2020 and then 4% in 2022, the average inflation target is met over the 2-year period, but is this truly “price stability”?

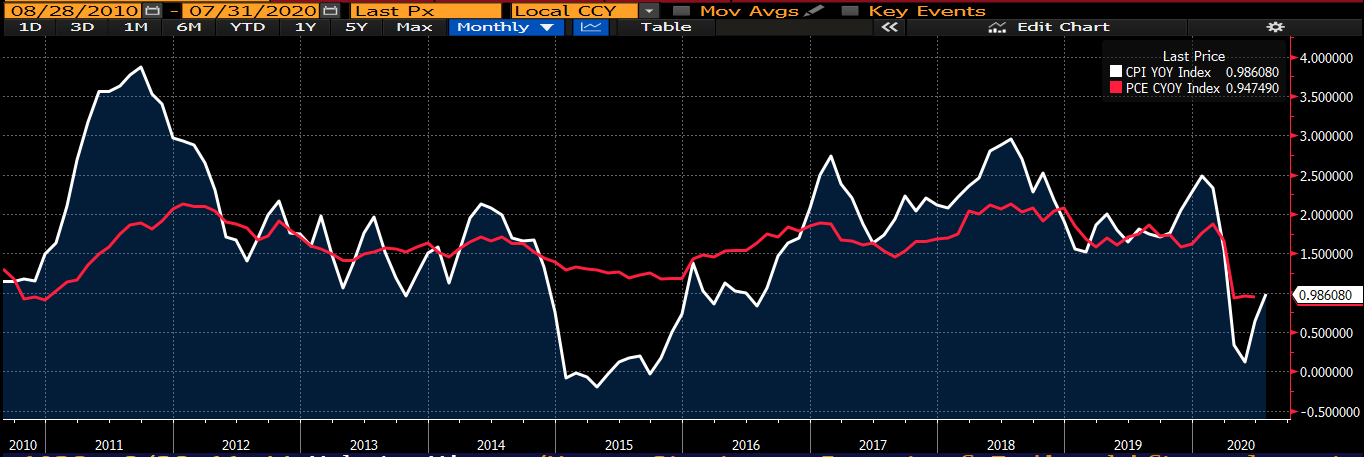

2. The Federal Reserve uses a different measure of inflation than we do in Australia. We use the Consumer Price Index (CPI), but the Fed follows Personal Consumption Expenditure “Core PCE” which excludes “volatile” seasonal food and energy price movements.

Sounds silly to exclude energy and food which are large parts of household budgets, but economists justify this because these “consumption expenditures” are not influenced by monetary policy.

i.e. we buy them with no regard to monetary policy because they’re necessities.

Below chart depicts US CPI (white) versus US Core PCE (red) over the last ten years.

Source: Bloomberg

3. In relation to (2), we forget that price increases of goods and services (inflation) hurts lowest income earners the most. Letting inflation rise above 2% for a period so that it averages 2% hurts the bottom 40% of income earners the most. This results in lower “real” wages which is a depressant on economic growth and hurts future inflation outcomes.

This cycle becomes reinforcing as most stimulus is then required to get national inflation rates higher…

4. Higher inflation does not mean higher economic output.

An economy can grow at 2% if inflation is at 0% or 5%, as GDP figures ignore price movements year-to-year. The extra erosion of purchasing power through inflation (higher inflation means your savings buy less goods/services) doesn’t translate to more economic output. If so, what’s the point?

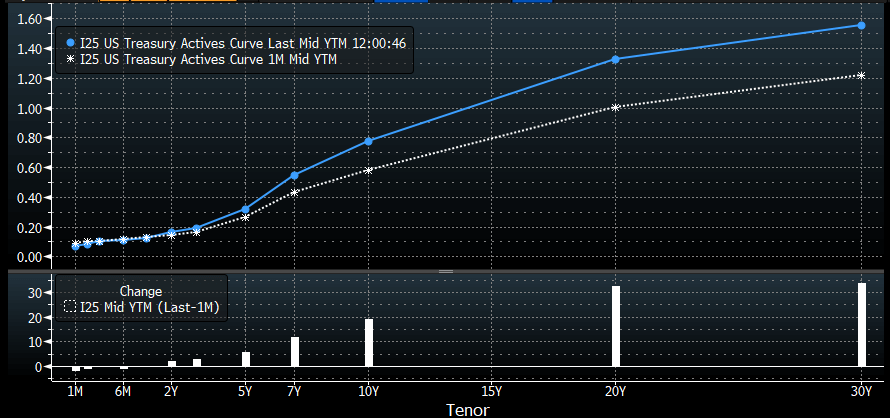

5. Longer term interest rates are not going to sit still and let inflation run higher.

Bond markets will likely sell-off if higher inflation is perceived to be a threat.

In the US economy, this will decelerate growth in their property market and expose US corporations to re-financing risk due to higher borrowing costs.

In fact, longer-term US bonds have already sold off over the last 1 month based upon rhetoric of higher inflation and the mammoth US government funding task.

Below I compare the US yield curve 1 month ago (white) compared to current (blue).

Source: Bloomberg

6. The value of the US dollar (USD) will move lower if allowing inflation to run hot which further reduces the purchasing power of a consumer dependent economy.

In 2019, personal consumption was 70% of the US economy or $13.28 trillion USD of spending.

While a lower USD makes US exports more competitive, it makes importing foreign goods less attractive as USD buy less of a foreign currency (assuming the foreign currency remains stable).

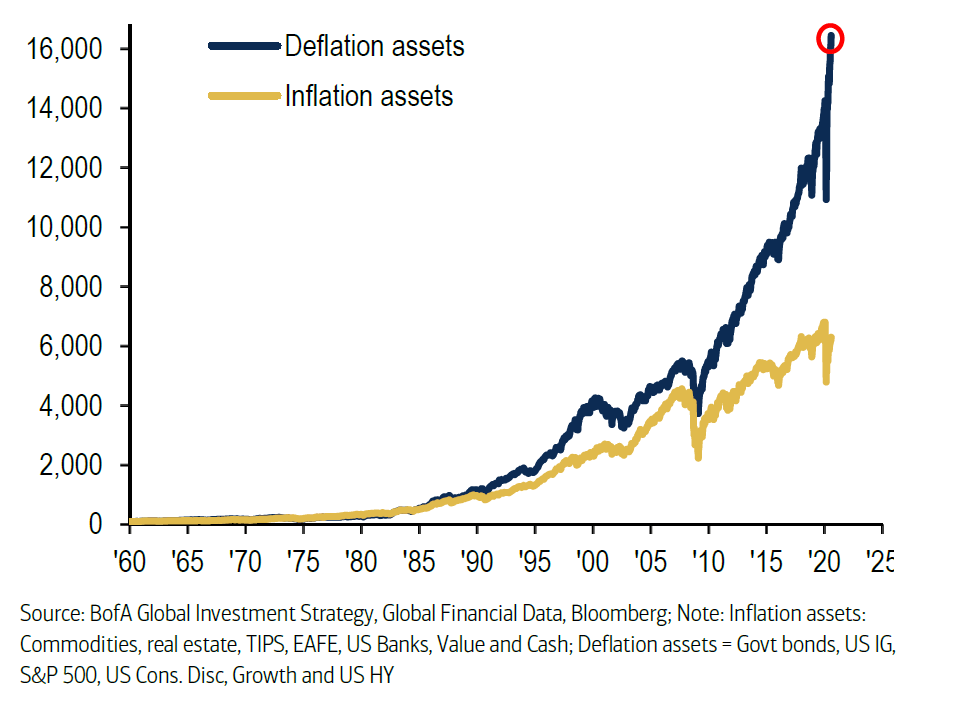

7. Higher inflation hurts profit margins of businesses that are unable to pass on the higher costs to their clients.

See below graphic from Bank of America, comparing the relative performance of what they deem “inflationary assets” versus “deflationary”. A.k.a assets that perform (rally) through higher inflation versus disinflation or deflation. US equities are considered deflationary assets by their grouping.

8. The starting point of this “inflation symmetry” target is completely arbitrary.

If we use 1980, then average inflation has been 2.7% and the Fed’s target is achieved.

If we use 1990, the average is 1.9% and 0.1% off target is very good.

If we use 2000, the average is 1.72% and the period includes the 2001 recession, 2007/2008 recession and current 2020 recession. Still pretty good!

And if we use Core CPI instead of Core PCE since 2000, then inflation has average 2%, target achieved!

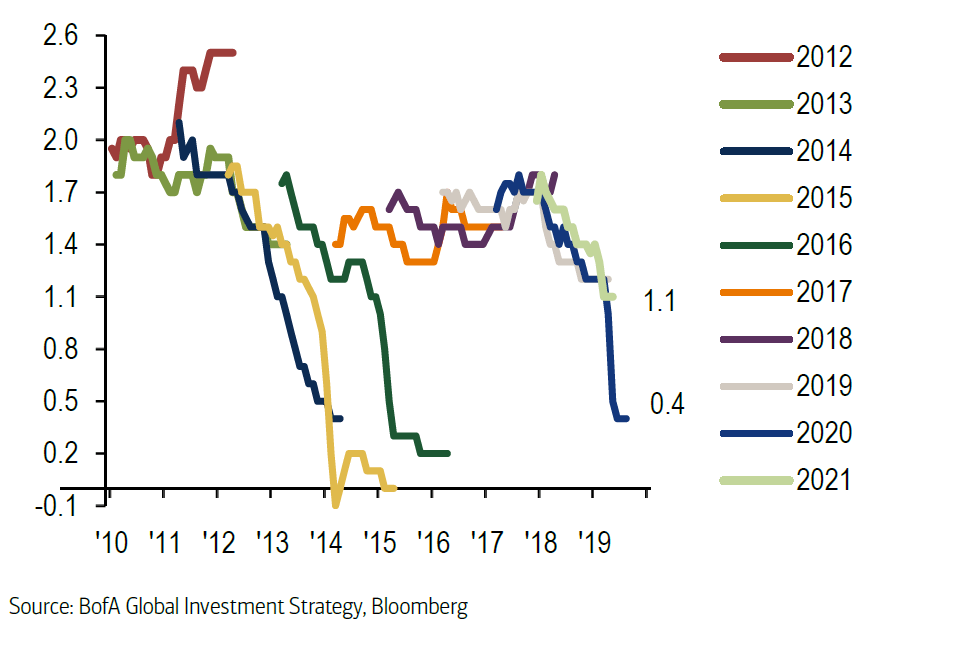

9. All the above analysis assumes that inflation will even get above 2% for a sustained period…which the Fed has been unable to do for the last twenty years. I would argue that’s because of disinflationary factors of debt, demographic decline and technology-led price deflation.

If they can’t achieve their target inflation rate now, we may be getting ahead of ourselves assuming they will in the future.

See below chart from Bank of America, highlighting how inflation has consistently “surprised” to the downside each year.

10. Finally, the current “accommodative” monetary policy setting of zero% interest rates and massive asset purchases (“QE”) is because of COVID-19.

If this is the case, then the return of policy to pre-COVID levels should be a factor of infection and mortality rates, and industries being able to return to normal operations – rather than inflation rates?

Closing remarks

While I have spent the last 1,000 words maligning the Federal Reserve for their tweaking of policy interpretation, I understand why they are doing it.

They have failed to meet their objectives for years and after years of underperformance. They are moving the goalposts to try and make things easier in future.

And all of this is in such strong contrast to our RBA, who takes a different approach.

In closing, I reiterate the comments of former RBA Governor Glenn Stevens in his final public address in 2016:

“I can recall being asked by an IMF official during the mid 1990s whether, if inflation rose above target, we were prepared to create a recession to get it down again. The implication was that we should be. We insisted on not being obliged to have a recession to shave a few tenths of a percentage point off inflation in a short period. We were not believers in the idea of destroying the world to save it.”

Have a great week.

*Noting all inflation rates are represented as a percentage per annum, i.e. 2% per annum

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.