And it pains me so much to tell you,

That you don’t know me that well…

Nelly Furtado (2000)

[Today is part 1 in a two-part series regarding bank funding and capital – today’s topic being about funding and part 2 being published next Monday, 21 September on capital]

If someone asked me to tell them how a mobile phone works, I would have little idea.

I know it’s a complex piece of hardware involving circuitry, receivers and responders for radio waves, and some minute computer that powers applications and functionality – but other than this broad level of knowledge, I have no knowledge of the inner machinations.

I hear similar questions about how banks fund themselves.

This comes in the form of questions regarding net interest margins and capitalisation, which are a key part of a bank’s profitability, and the sustainability of their business.

In general, bank funding is a representation of their client’s economic activities, which shapes outcomes for how treasury departments deploy funds to manage short to longer term financing.

For example, if a bank such as CBA has a large amount of deposits, then it represents that their client base has savings.

How they price those deposits versus the loans they originate will determine their Net Interest Margin (NIM) and has flow-on effects to other areas of interest.

Deposits

Deposits are at the heart of banking, as Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions (ADIs) are empowered by APRA to take deposits (a legally defined word) as well as make advances (loans) against funds held in reserve (liabilities).

At present, Australian ADIs fund themselves with a focus on “sticky” retail deposits, which make up the majority of their funding.

The exact mix will differ from ADI to ADI, as some banking institutions have more complex business lines and in general, the larger banks have competitive advantage through greater access to capital markets to fund themselves.

For example, our “Big 4” – CBA, ANZ, NAB and WBC – have more diverse funding allocations due to their size and scale, but also their larger geographic footprint.

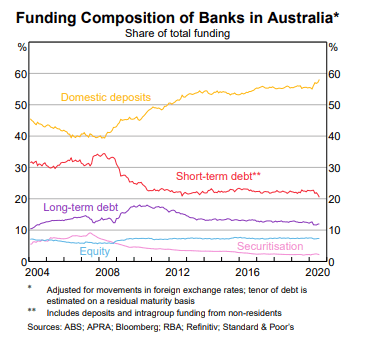

The Australian retail deposit market was shaken up after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007/2008, where there was increased focus on domestic deposits, as opposed to more fickle wholesale and international short-term funding markets.

Prior to the GFC, short-term debt issuance was more economic for ADIs who would issue shorter dated debt (a liability) and invest in assets (issuing mortgages or buying longer term bonds) at higher yields. This was something that worked when the yield curve was positively sloped and when there was abundant access to capital markets and hedging.

Along came the GFC and capital markets dried up, and banks had little access to this funding.

As the GFC was a credit crisis, global investors and banking houses did not want to lend to one another, so the banks had to seek the higher cost of retail deposit funding to ensure business continuity.

This process was formalised by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), with the Basel III Capital Reforms of 2013 establishing certain regulatory guidelines and ratios.

APRA adopted these guidelines to make our ADIs more robust than they previously were.

Funding profile – a CBA example

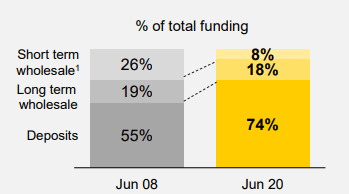

As at 30 June 2020, CBA has seen an increased weighting to retail customer deposits.

Source: CBA

This increase from 55% to 74% has been due to their need to source more stable funding, the Basel III regulatory framework, but also clients increasing their savings rates during COVID-19.

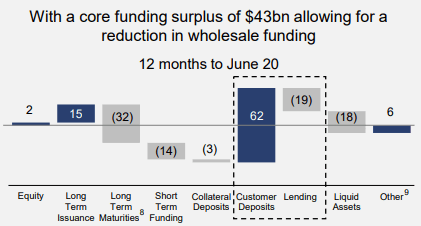

This increase in “precautionary savings” has led to CBA having a funding surplus of 43bln as at 30 June 2020. Part of the reason – along with the other Major Banks – is that there’s very little planned bond issuance until these deposit levels recede.

Literally, they have excess funding.

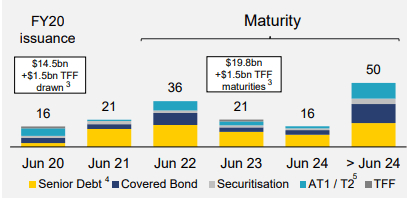

Source: CBA

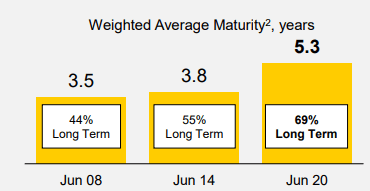

Another shift due to Basel III was a ratio called Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) which required many ADIs to increase the tenor of their wholesale debt issuance (bonds) to longer maturities.

This was to reduce ADI’s asset/liability duration gap.

I.e. if writing 30-year mortgages (assets) then they should not be funding these mortgages through only short-term debt issuance, where the “duration” gap is 20-30 years and open to reinvestment and market risk.

This means less focus on short-term debt issuance.

Source: CBA

In CBA’s case, not only did they extend the weighted average maturity of their debt, they have spread their maturities across more years, making their maturity profile less lumpy.

Source: CBA

Lowest Cost Funding

Part of the outcome of Basel III reforms cemented that ADIs are not able to only choose the lowest cost of funding available to them at the time, but they must have a diversified and stable funding profile.

This reliance on domestic deposits, especially retail deposits, is a trend likely to continue for many years to come.

Also, what used to be expensive funding is now much cheaper.

For example, more than 150 billion AUD of CBA’s deposits now yield 0% or close to 0%, as cheap funding as a bank could ask for.

However, as cash at banks is an overnight liability – it can be withdrawn at a moment’s notice – ADIs must still fund themselves via longer-term and generally higher cost sources, to fulfil their NSFR.

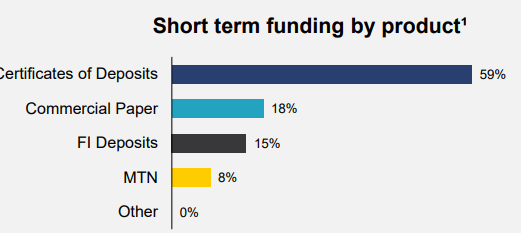

For example, CBA elects to utilise many short-term products (“money market”) securities:

Source: CBA

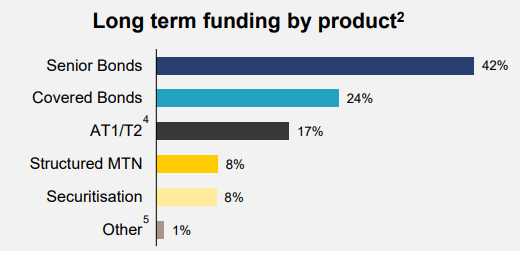

And in longer-term examples they have many more options yet again:

Source: CBA

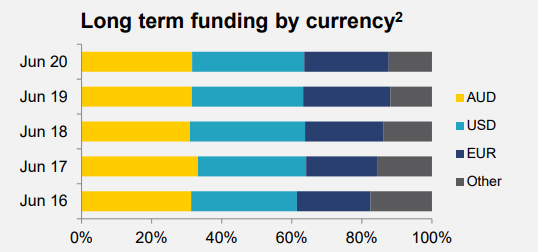

And within their longer-term funding profile, CBA has diversified the source by currency – often issuing in American and European markets to obtain funding from foreign investors that typically do not buy AUD debt securities. i.e. diversifying their funding by source and geography.

Source: CBA

Breaking down the numbers, CBA has 115bln AUD of debt outstanding:

69% of this is “long term” or 79.35bln

31% of this is “short term” or 35.65bln

And have 43bln of surplus funding still available, allowing them to reduce their wholesale funding over the coming years, or until deposits recede or lending volumes pick up.

Deal pipeline

This surplus funding is why our Big 4 and selective other Aussie banks have no need to issue new wholesale debt, where their Net Stable Funding Ratios are fulfilled.

This lack of forthcoming supply, where there is a net supply decrease as existing deals are being matured and not re-financed, has created a structural underpinning of domestic bond markets.

Not only are Australian bonds a source of higher yield when compared to other developed nations – many have 0% or negative cash rates, and flatter yield curves – but we have less corporate debt issuance forecasted for the short to medium term.

This net decrease in supply from the Big 4, coupled with increased demand due to uncertainty and increase in defensive asset allocations, has seen a strong, structural bid for existing Australian bonds.

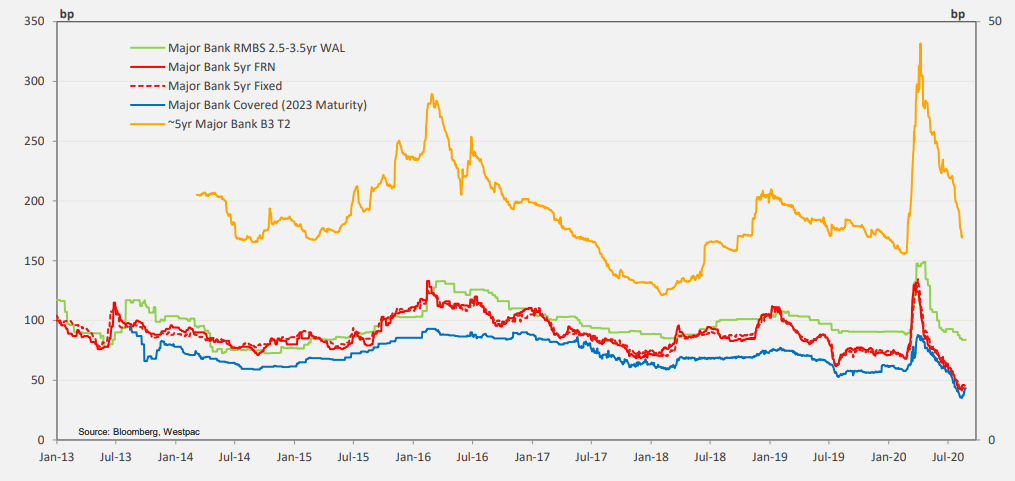

This has already manifested in a tightening of credit spreads (a rally) across Major Bank senior unsecured debt, both fixed and floating rate debt types.

Source: Westpac

However, this rally has not been fully realised in other Australian debt securities, such as RMBS and Tier-2 (subordinated), with yields back to their pre-COVID levels, but not reflecting the new monetary accommodation of the RBA, nor the lack of forthcoming supply.

When I wrote both Volatility and Liquidity and Stairway to Heaven, I wanted to emphasise the importance of investor psychology and being mentally nimble, allowing an investor to be “selectively long.”

What I mean by selectively long is to be invested or “long” without necessarily being bullish – or being bullish about selective securities or market sectors without being bullish about the overall market.

As such, I still see value in such areas of fixed income markets, where markets have room to rally further.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.