Prelude

In order to provide you daily content in our morning notes, we are usually organised ~2 weeks in advance with lists of topics and thematics that we hope will resonate with you.

Originally, I had planned to write this note about inflation and why I’m forecasting cost-push inflation to pickup through the reconstruction of supply chains in response to COVID but also the US-China trade war.

I actually wrote said note, but after seeing Max’s gem yesterday about the current liquidity “trap” I changed my mind and wrote the below. Hope you enjoy!

The rise of China and the importance of demography created a sweet spot that has dictated the path of inflation, interest rates and social equality over the past three decades.

But the future will not be anything like the past, and we’re at or nearing a point of inflection.

This is why it’s so important to have detailed knowledge of our modern history, in which trends are slowly but surely reversing.

In advance, for those wanting to read more on this topic, I encourage you to buy the latest book by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan, titled “The Great Demographic Reversal”.

The Rise of China

The single most impactful factor to global markets (both labour and capital) over the last three decades was the integration of China into the global economy.

When Deng Xiaoping reversed Mao Zedong’s policies of the 80s by combining both socialist ideology with an economy opening to relatively “freer” capital markets, this led to China’s eventual inclusion in the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1997.

This development more than doubled the available supply of labour to global manufacturing companies, adding more than 240mio eligible working age persons to the global labour force.

Eastern Europe

Next came the collapse of the USSR, signified by the toppling of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

This brought about the reintegration of Eastern Europe, primarily the Baltic States from Poland down to Bulgaria, back into the European labour force, estimated to have been around 209mio people at the time.

Falling dependency ratios

During this 1990-2019 time period, there was a rise in the number of workers relative to the population – basically more people aged 15-64.

This came about through a change in demographics where Baby Boomers and Generation X had entered the work force (increasing labour supply), but also when female participation within domestic labour markets was increasing.

In addition to these demographic changes contributing to an increase in the global labour markets, this was also at a time where outsourcing became more commonly accepted as a business practice.

The greatest ever labour supply increase

The combination of the rise of China, reincorporation of Europe post USSR, increased globalisation (outsourcing), together with the Baby Boomer generations population bulge, improvement of the working age population and greater employment of women, created the largest ever positive supply shock to global labour markets.

The effective labour supply available to advanced economies more than doubled over this three decade period.

The effects of great labour supply

In hindsight, it’s inevitable that such a positive supply shock to labour markets saw a wide-spread weakening in the collective bargaining power of the labour force, resulting in a period of stagnant and persistently low wage growth.

In advanced economies, this was disproportionately felt within the “unskilled” labour category, where companies outsourced manufacturing and industrial production to cheaper substitutes – specifically China, India, Philippines etc.

This saw an increase in social inequality, where unskilled (non-degree qualified) labourers saw lower wage growth relative to skilled labour. The proverbial “the rich get richer, the poor get poorer”.

Both a symptom and also a cause of labour’s declining bargaining power was a decline in trade union membership, which was common throughout advanced economies.

Deflationary forces

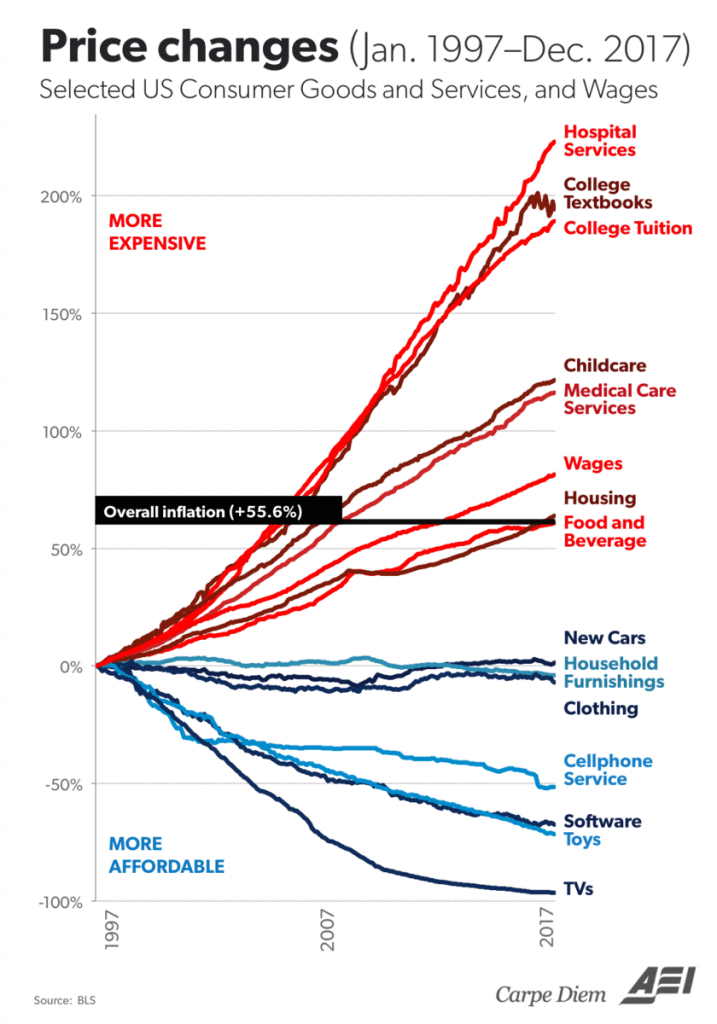

We can see evidence of these deflationary forces in action in the statistic bureau’s measurement of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket.

Durable goods manufacturing has seen price declines reliably over the last 30 years, as has the decreased costs of technology such as TVs, computers and mobile phones.

The deflationary elements of this labour supply shock have seen reduced inflation expectations, and why I titled this piece “Demographics are Destiny”.

The result

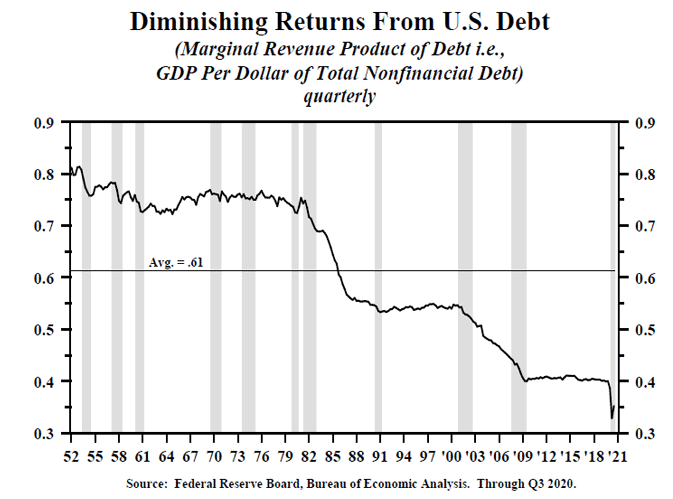

We’ve tried to offset these deflationary factors with credit expansion and low interest rate policy, seeking to revive the “animal spirits” of the market to borrow, consume and invest to achieve higher rates of return or standards of living.

This debt expansion produced lower and lower marginal benefit or return on investment, which created a cycle of expanding debt to seek higher returns, with lower returns.

Why do central banks keep stimulating?

Central banks are mostly government agencies, mandated to achieve certain aspects of currency and price stability, and to maximise employment.

Because of this mandate, central banks have to keep enlarging their stimulatory efforts to hit unachievable targets – because of our past demographic destinies and other factors outside their control (COVID).

The inflection point

I believe we’re nearing an inflection point, where these deflationary trends are coming to an end.

These deflationary trends are not short-term., They are longer-term structural trends that will affect economies for years and decades into the future.

Because these are structural trends rather than short-term cyclical economic impulses, we tend to ignore them because they don’t conform to our short to medium-term investment biases.

#1 The first change is that China is no longer exporting deflation globally, as their share of global manufacturing declines and their rural to urban population migration slows down. This isn’t an overtly inflationary impulse, but it’s less deflationary.

The other factor within China is that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is seeking to refine their economic output to a model more akin to other developed economies, with greater emphasis on domestic consumption and internalisation.

This increase on consumption expenditure will provide inflationary elements to global demand for goods and services (particularly services).

#2 The second change is that global dependency ratios are now increasing each year because of aging population without corresponding increases in retirement ages. Historically, a country’s retirement age was set at life expectancy minus 10-15 years. Hence in Australia when our life expectancy was 72-74 years per person, our retirement age was set at 60 years old.

As life expectancies have extended another 5-10 years, retirement ages have barely moved.

As the Baby Boomer generation enters retirement – a trend that began around 2010 – this greater dependency has and is creating a significant liability for the working age population to contribute a higher portion of their income via taxes, in order to pay for government spending programs.

The way out of this is through population growth – increasing birth rates or increasing migration.

This aging population dynamic directly ties into greater demand for healthcare services as an increasing portion of household expenditure will be allocated to health services, generally a more inflationary expense for budgets.

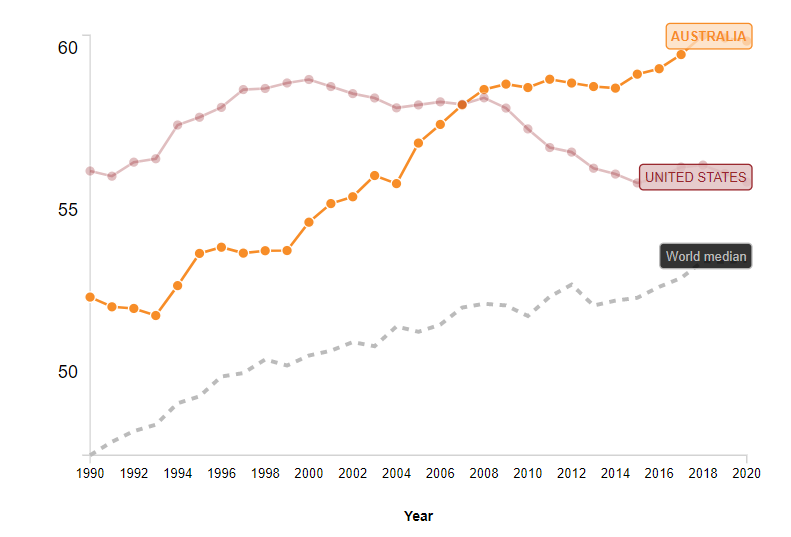

#3 Increased female employment has largely peaked in advanced economies, though several countries such as the USA saw no marginal improvement over the 30-year period.

Recent economic releases have also shown that female employment has declined immensely in 2020, as mobility restrictions affected female employment disproportionally to male employment, where females were more likely to discontinue working in order to maintain children and households.

#4 Lastly, COVID has taught us the importance of supply chain integrity and changed our focus from cost minimisation of businesses operations, to minimising supply chain disruption, even if it is at a higher cost. In fact, it’ll likely be at a higher cost (inflationary).

This stems from both the internationalisation of Chinese consumption, the US-China trade war and tariffs on certain Chinese companies, logistic disruptions from COVID-19 impacts, but future proofing supply chains for these unknown externalities that will inevitably affect our global economy again.

Closing remarks

There are many long-term trends mentioned within today’s note that will affect global capital markets, supply of goods and services, inflation, government budgets and taxation, central bank policy and much more.

Because of our focus on short to medium term investment horizons, we can oft miss analysing these trends, because they don’t conform to our relevant time periods of purview.

However, by taking a step back and reviewing the long-term trends, we can position portfolios with longer-term horizons for success.

We’ll be following today’s note up with the applicable investment thematics that align with these trends next Monday.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.